In this fourth part of this introductory series, we will look at the Food Forest. What is it? How do you design it? And what does it need to thrive?

What is a Food Forest?

Also known as a Forest Garden, a Food Forest is a diverse eco-system of edible plants. It is designed with the same patterns and functions of naturally occurring eco-systems. You will not find neat equidistant spaced rows in a Forest Garden, but a verdant bursting of life in all directions. It’s 3-dimensional with growth spreading up, down and all around.

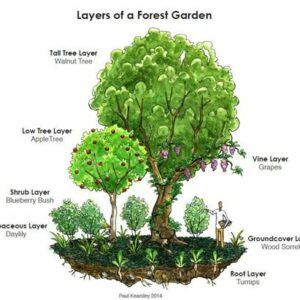

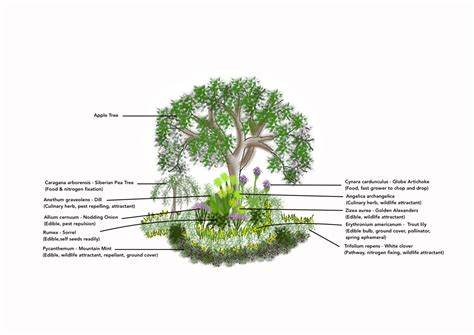

A Food Forest has many layers. There is the overstory, which is the big main centerpiece tree…or two, or three. The understory is comprised of dwarf trees and/or shrubs. The herbaceous layer is just what it sounds like, as are the root layers, the ground cover layers and the vine layers. The mycelial layers are the mushrooms, both blooming above ground and spreading their connections underground.

With multiple layers, more plants can fit into an area. There is no competition between them, only cooperation, as they all have different needs and form wonderfully symbiotic connections to each

other.

How To Design a Food Forest Garden

This is a multi-stage, on-going project. It’s a living thing. Nature does not have laws, only tendencies. So, obviously, there’s no one-size-fits-all formula. As always, it is a framework on how to plan it out. Or, how to plan your planning!

Remember to design for succession and develop a clear sense of the direction you want to take it. The basic succession proceeds from disturbed ground to pioneer plants, then various grasses and other plants come in, then small woody shrubs, then larger trees and finally, the big trees of a mature closed canopy forest.

Remember to design for succession and develop a clear sense of the direction you want to take it. The basic succession proceeds from disturbed ground to pioneer plants, then various grasses and other plants come in, then small woody shrubs, then larger trees and finally, the big trees of a mature closed canopy forest.

And you don’t have to go all the way. You probably won’t live long enough anyway. When it’s naturally occurring, this is a 50 to 150 year process. (Assuming nobody prevents it.) Instead, think about your ultimate goals. Don’t fall into analysis paralysis, but definitely set some clear goals.

What are your reasons for doing this? Is it for self-reliance? An income? Having the healthiest food for your family? Educating people? Or is it just totally fascinating to you?

Obviously, you don’t have to limit yourself to one of these reasons. But if you can prioritize them, it will help you with the direction of your research and design.

If self-reliance and/or educating people is your priority, designing with the most diversity for food and medicine

will be the way to go. But if you want to make a living from it, you should know what crops

will both grow and sell the best in your area. And these can certainly be combined. You can have a well fed family, sell your produce at the farmers market, where you hand out brochures for you permaculture classes and be totally self reliant.

Knowing what grows in your area is important, so visiting nearby woodland areas will give you valuable insight. What species and communities of species do you find there? If you stroll through the woods and

find elderberry, hawthorne and crabapple trees, then you have a good place to start. Expand out from there to devise your plant list. This is something that will be on-going as well. Like a business plan. It’ll keep getting bigger, more subtle and different, the more you learn.

Depending on the size of your property and the complexity of your goals you might want to do an actual site survey. At the very least, draw out your plans on a napkin. The surrounding area has a definitive say in

your design, too. If your property is surrounded by BLM land you will have a very different design than if you are surrounded by typical suburban lots.

If you’re a science geek, you might want to get some soil analysis done. This certainly is not necessary. But information is always a good thing. If it seems like too much of a pain in the neck, don’t bother. Nature remediates everything, whether we know about the soil composition or not.

Design your infrastructure first. This is all the stuff that would be unbearably difficult to move later.

Water is the most important. Water tanks, irrigation lines, swales, ponds need to be in place. Or at least have a place marked out for them. Of course you can add small, hand dug swales later. But if your site

needs some big ones, this is the time to do it. If you’re going to dig a pond, advice from the bulldozer guy would be helpful. Especially if you will need him to shape your roads. Doing those two things together might be the most efficient.

After that comes pathways, fences, sheds, chicken houses and barns. And always keep in mind the size of your future full grown trees. Once you get the basics laid out, then comes the fun part! Then you can add your plants!

Don’t try to do too much at one time. Even if your property is small, it’s still a huge project. Just focus on one or two aspects of it at a time. Do things in logical stages. First comes dirt. Are you starting in the desert, where there is no dirt? Then you need dirt. You need organic stuff mixed into the sand with decomposers to eat it. You need cover crops. You need pioneer plants. You need shade and wind protection.

Or maybe there’s already some nice stuff growing there. A meadow maybe, with some lovely old trees. Nitrogen fixers, compost and compost teas are always a good idea. You can scatter cover crop seeds amongst the wildflowers. Soil amendment is super important. Waiting until the second year to plant could actually end up saving you time.

But first, there’s some important information you need to know about trees.

The Fungal-Bacterial Ratio

Trees and fungi go together. In a healthy forest ecology the soil has  anywhere from 10 to 50 times as much fungi as bacteria. And you certainly can re-create this. Add fungi spore. Red and/or crimson clover helps, too, as they both have strong affinities for micorrhizal fungi. Woody mulch is a favorite food for fungus, so give them a lot of it, above ground and below. Oyster mushrooms really love straw.

anywhere from 10 to 50 times as much fungi as bacteria. And you certainly can re-create this. Add fungi spore. Red and/or crimson clover helps, too, as they both have strong affinities for micorrhizal fungi. Woody mulch is a favorite food for fungus, so give them a lot of it, above ground and below. Oyster mushrooms really love straw.

In a very small nutshell, when you make compost, you need nitrogen and carbon. Generally, the carbon should outnumber the nitrogen by a ratio of 30:1. Or even as high as 300:1. You don’t need to measure. Just keep dumping in more carbon.

The nitrogen is shit, dead bodies, food scraps, and nitrogen fixing green manure cover crops turned under. And carbon is straw, sawdust, leaves, grass clippings, woodchips. Fungi eat carbon and bacteria eat nitrogen. Both are necessary, but different plants like different proportions.

Annual vegetables like an even 1:1 mix of fungi to bacteria, whereas for trees the ratio is much higher. 10:1 or even 50:1, as already stated. So you can see how, this too, is a succession. Rather, it is an integral part of the succession process. This is one of the ways you

can accelerate succession.

For successful tree crops, you’ll want to encourage the spread of fungi. But be careful. You can accelerate the process, but you don’t want to be ridiculous about it. Keep dumping on woody mulch. Fungus is exciting but don’t forget about the need for bacteria. Fungi and bacteria are both incredibly important for healthy soil. Not to mention earthworms, beetles and arthropods who also have multiple functions in living, healthy soil. They decompose organic matter, aerate the soil, make nutrients available, prevent nutrient leaching and so much more.

This is what’s wrong with food bought at the grocery store. It’s planted in dead soil and fed a diet of fake fertilizer. And then people wonder why they’re chronically ill. Organic gardeners know the importance of living, health soil that’s teeming with life. It’s pretty simple. Do a lot of mulching and composting. Avoid

disturbing the soil. Give the soil organisms what they need to thrive. It only starts to get complicated, overwhelming even, when we delve into the details. This is why it’s important to focus on small changes. Keep researching. Keep learning. But don’t make yourself crazy in the process.

In Conclusion

So we focused on some of the main processes of starting a food forest, along with a little bit of a dive into the fungal/bacterial ratio. I tried to avoid getting too complicated. I hope you found it interesting and inspirational. I hope you start a permaculture garden and help encourage others to do the same. It can save the planet. Please leave a comment. I would love to hear about your aspirations and to connect.

Hi there,

Thank you for sharing this informative article on permaculture design and food forests. It’s clear that permaculture design can be a powerful tool for creating sustainable and regenerative ecosystems, and your explanation of the principles behind food forests was particularly helpful.

As I was reading this article, one question that came to mind was: how can we scale up permaculture design and food forests to meet the needs of a growing global population? It’s clear that these principles have the potential to create more sustainable and regenerative food systems, but can they be implemented on a large enough scale to make a significant impact?

This is a complex and challenging question, but one that I believe is essential to consider as we work towards creating a more sustainable and equitable future. Perhaps part of the answer lies in education and advocacy, helping more people understand the principles behind permaculture design and the benefits of food forests.

Hi Dave

Absolutely. And it is being scaled up. Not enough to feed the entire world, at this point. But Rome wasn’t built in a day, either. There’s a lot of momentum in the wrong direction and it won’t stop without being made to stop.

There are several Re-Greening the Desert operations in effect around the world. If you were to do a search for that in Youtube, you would find many hours of REALLY inspirational viewing. There are also a lot of college courses in large scale regenerative agriculture. So things are changing.

But, like you say, education and advocacy. Which is why I’m doing this. 🙂

Thanks for your thoughtful comment and have a great day!

Anna

I appreciate the step-by-step explanation and the helpful visuals provided. Your personal experience with creating a food forest also adds a valuable perspective. I’m curious about the maintenance of a food forest…any advice on how much pruning and upkeep is necessary, and how to prevent pests and disease without using harmful chemicals?

Hi Ronnie

Thanks for your comment.

Pruning, like everything else in permaculture design, depends on what it depends on. Maybe you want an open pruning to let in more light for the understory. Or maybe you want a dense canopy for the shade lovers yo have underneath. There are no hard and fast rules. It just depends on what you, the particular trees and the property in general needs.

As to pests, if you have a broad enough variety of plants…that attract predatory and parasitic insects…and a no large areas planted in only one thing, the pests will all get eaten. No poison necessary!

Anna